|

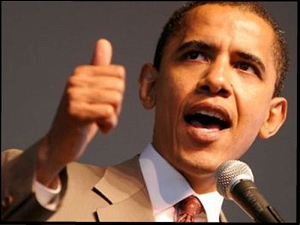

Way Forward in Iraq Remarks - Chicago Council on Global Affairs |

TOPIC: Iraq November 20, 2006 A Way Forward in Iraq Remarks Chicago Council on Global Affairs Complete Text Throughout American history, there have been moments that call on us to meet the challenges of an uncertain world, and pay whatever price is required to secure our freedom. They are the soul-trying times our forbearers spoke of, when the ease of complacency and self-interest must give way to the more difficult task of rendering judgment on what is best for the nation and for posterity, and then acting on that judgment ? making the hard choices and sacrifices necessary to uphold our most deeply held values and ideals. This was true for those who went to Lexington and Concord. It was true for those who lie buried at Gettysburg. It was true for those who built democracy’s arsenal to vanquish fascism, and who then built a series of alliances and a world order that would ultimately defeat communism. And this has been true for those of us who looked on the rubble and ashes of 9/11, and made a solemn pledge that such an atrocity would never again happen on United States soil; that we would do whatever it took to hunt down those responsible, and use every tool at our disposal ? diplomatic, economic, and military ? to root out both the agents of terrorism and the conditions that helped breed it. In each case, what has been required to meet the challenges we face has been good judgment and clear vision from our leaders, and a fundamental seriousness and engagement on the part of the American people ? a willingness on the part of each of us to look past what is petty and small and sensational, and look ahead to what is necessary and purposeful. A few Tuesdays ago, the American people embraced this seriousness with regards to America’s policy in Iraq. Americans were originally persuaded by the President to go to war in part because of the threat of weapons of mass destruction, and in part because they were told that it would help reduce the threat of international terrorism. Neither turned out to be true. And now, after three long years of watching the same back and forth in Washington, the American people have sent a clear message that the days of using the war on terror as a political football are over. That policy-by-slogan will no longer pass as an acceptable form of debate in this country. “Mission Accomplished,” “cut and run,” “stay the course” ? the American people have determined that all these phrases have become meaningless in the face of a conflict that grows more deadly and chaotic with each passing day ? a conflict that has only increased the terrorist threat it was supposed to help contain. 2,867 Americans have now died in this war. Thousands more have suffered wounds that will last a lifetime. Iraq is descending into chaos based on ethnic divisions that were around long before American troops arrived. The conflict has left us distracted from containing the world’s growing threats ? in North Korea, in Iran, and in Afghanistan. And a report by our own intelligence agencies has concluded that al Qaeda is successfully using the war in Iraq to recruit a new generation of terrorists for its war on America. These are serious times for our country, and with their votes two weeks ago, Americans demanded a feasible strategy with defined goals in Iraq ? a strategy no longer driven by ideology and politics, but one that is based on a realistic assessment of the sobering facts on the ground and our interests in the region. This kind of realism has been missing since the very conception of this war, and it is what led me to publicly oppose it in 2002. The notion that Iraq would quickly and easily become a bulwark of flourishing democracy in the Middle East was not a plan for victory, but an ideological fantasy. I said then and believe now that Saddam Hussein was a ruthless dictator who craved weapons of mass destruction but posed no imminent threat to the United States; that a war in Iraq would harm, not help, our efforts to defeat al Qaeda and finish the job in Afghanistan; and that an invasion would require an occupation of undetermined length, at undetermined cost, with undetermined consequences. Month after month, and then year after year, I’ve watched with a heavy heart as my deepest suspicions about this war’s conception have been confirmed and exacerbated in its disastrous implementation. No matter how bad it gets, we are told to wait, and not ask questions. We have been assured that the insurgency is in its last throes. We have been told that progress is just around the corner, and that when the Iraqis stand up, we will be able to stand down. Last week, without a trace of irony, the President even chose Vietnam as the backdrop for remarks counseling “patience” with his policies in Iraq. When I came here and gave a speech on this war a year ago, I suggested that we begin to move towards a phased redeployment of American troops from Iraqi soil. At that point, seventy-five U.S. Senators, Republican and Democrat, including myself, had also voted in favor of a resolution demanding that 2006 be a year of significant transition in Iraq. What we have seen instead is a year of significant deterioration. A year in which well-respected Republicans like John Warner, former Administration officials like Colin Powell, generals who have served in Iraq, and intelligence experts have all said that what we are doing is not working. A year that is ending with an attempt by the bipartisan Iraq Study Group to determine what can be done about a country that is quickly spiraling out of control. According to our own Pentagon, the situation on the ground is now pointing towards chaos. Sectarian violence has reached an all-time high, and 365,000 Iraqis have fled their homes since the bombing of a Shia mosque in Samarra last February. 300,000 Iraqi security forces have supposedly been recruited and trained over the last two years, and yet American troop levels have not been reduced by a single soldier. The addition of 4,000 American troops in Baghdad has not succeeded in securing that increasingly perilous city. And polls show that almost two-thirds of all Iraqis now sympathize with attacks on American soldiers. Prime Minister Maliki is not making our job easier. In just the past three weeks, he has ? and I’m quoting from a New York Times article here ? “rejected the notion of an American ‘timeline’ for action on urgent Iraqi political issues; ordered American commanders to lift checkpoints they had set up around the Shiite district of Sadr City to hunt for a kidnapped American soldier and a fugitive Shiite death squad leader; and blamed the Americans for the deteriorating security situation in Iraq.” This is now the reality of Iraq. Now, I am hopeful that the Iraq Study Group emerges next month with a series of proposals around which we can begin to build a bipartisan consensus. I am committed to working with this White House and any of my colleagues in the months to come to craft such a consensus. And I believe that it remains possible to salvage an acceptable outcome to this long and misguided war. But it will not be easy. For the fact is that there are no good options left in this war. There are no options that do not carry significant risks. And so the question is not whether there is some magic formula for success, or guarantee against failure, in Iraq. Rather, the question is what strategies, imperfect though they may be, are most likely to achieve the best outcome in Iraq, one that will ultimately put us on a more effective course to deal with international terrorism, nuclear proliferation, and other critical threats to our security. What is absolutely clear is that it is not enough for the President to respond to Iraq’s reality by saying that he is “open to” or “interested in” new ideas while acting as if all that’s required is doing more of the same. It is not enough for him to simply lay out benchmarks for progress with no consequences attached for failing to meet them. And it is not enough for the President to tell us that victory in this war is simply a matter of American resolve. The American people have been extraordinarily resolved. They have seen their sons and daughters killed or wounded in the streets of Fallujah. They have spent hundreds of billions of their hard-earned dollars on this effort ? money that could have been devoted to strengthening our homeland security and our competitive standing as a nation. No, it has not been a failure of resolve that has led us to this chaos, but a failure of strategy ? and that strategy must change. It may be politically advantageous for the President to simply define victory as staying and defeat as leaving, but it prevents a serious conversation about the realistic objectives we can still achieve in Iraq. Dreams of democracy and hopes for a perfect government are now just that ? dreams and hopes. We must instead turn our focus to those concrete objectives that are possible to attain ? namely, preventing Iraq from becoming what Afghanistan once was, maintaining our influence in the Middle East, and forging a political settlement to stop the sectarian violence so that our troops can come home. There is no reason to believe that more of the same will achieve these objectives in Iraq. And, while some have proposed escalating this war by adding thousands of more troops, there is little reason to believe that this will achieve these results either. It’s not clear that these troop levels are sustainable for a significant period of time, and according to our commanders on the ground, adding American forces will only relieve the Iraqis from doing more on their own. Moreover, without a coherent strategy or better cooperation from the Iraqis, we would only be putting more of our soldiers in the crossfire of a civil war. Let me underscore this point. The American soldiers I met when I traveled to Iraq this year were performing their duties with bravery, with brilliance, and without question. They are doing so today. They have battled insurgents, secured cities, and maintained some semblance of order in Iraq. But even as they have carried out their responsibilities with excellence and valor, they have also told me that there is no military solution to this war. Our troops can help suppress the violence, but they cannot solve its root causes. And all the troops in the world won’t be able to force Shia, Sunni, and Kurd to sit down at a table, resolve their differences, and forge a lasting peace. I have long said that the only solution in Iraq is a political one. To reach such a solution, we must communicate clearly and effectively to the factions in Iraq that the days of asking, urging, and waiting for them to take control of their own country are coming to an end. No more coddling, no more equivocation. Our best hope for success is to use the tools we have ? military, financial, diplomatic ? to pressure the Iraqi leadership to finally come to a political agreement between the warring factions that can create some sense of stability in the country and bring this conflict under control. The first part of this strategy begins by exerting the greatest leverage we have on the Iraqi government ? a phased redeployment of U.S. troops from Iraq on a timetable that would begin in four to six months. When I first advocated steps along these lines over a year ago, I had hoped that this phased redeployment could begin by the end of 2006. Such a timetable may now need to begin in 2007, but begin it must. For only through this phased redeployment can we send a clear message to the Iraqi factions that the U.S. is not going to hold together this country indefinitely ? that it will be up to them to form a viable government that can effectively run and secure Iraq. Let me be more specific. The President should announce to the Iraqi people that our policy will include a gradual and substantial reduction in U.S. forces. He should then work with our military commanders to map out the best plan for such a redeployment and determine precise levels and dates. When possible, this should be done in consultation with the Iraqi government ? but it should not depend on Iraqi approval. I am not suggesting that this timetable be overly-rigid. We cannot compromise the safety of our troops, and we should be willing to adjust to realities on the ground. The redeployment could be temporarily suspended if the parties in Iraq reach an effective political arrangement that stabilizes the situation and they offer us a clear and compelling rationale for maintaining certain troop levels. Moreover, it could be suspended if at any point U.S. commanders believe that a further reduction would put American troops in danger. Drawing down our troops in Iraq will allow us to redeploy additional troops to Northern Iraq and elsewhere in the region as an over-the-horizon force. This force could help prevent the conflict in Iraq from becoming a wider war, consolidate gains in Northern Iraq, reassure allies in the Gulf, allow our troops to strike directly at al Qaeda wherever it may exist, and demonstrate to international terrorist organizations that they have not driven us from the region. Perhaps most importantly, some of these troops could be redeployed to Afghanistan, where our lack of focus and commitment of resources has led to an increasing deterioration of the security situation there. The President’s decision to go to war in Iraq has had disastrous consequences for Afghanistan -- we have seen a fierce Taliban offensive, a spike in terrorist attacks, and a narcotrafficking problem spiral out of control. Instead of consolidating the gains made by the Karzai government, we are backsliding towards chaos. By redeploying from Iraq to Afghanistan, we will answer NATO’s call for more troops and provide a much-needed boost to this critical fight against terrorism. As a phased redeployment is executed, the majority of the U.S. troops remaining in Iraq should be dedicated to the critical, but less visible roles, of protecting logistics supply points, critical infrastructure, and American enclaves like the Green Zone, as well as acting as a rapid reaction force to respond to emergencies and go after terrorists. In such a scenario, it is conceivable that a significantly reduced U.S. force might remain in Iraq for a more extended period of time. But only if U.S. commanders think such a force would be effective; if there is substantial movement towards a political solution among Iraqi factions; if the Iraqi government showed a serious commitment to disbanding the militias; and if the Iraqi government asked us ? in a public and unambiguous way ? for such continued support. We would make clear in such a scenario that the United States would not be maintaining permanent military bases in Iraq, but would do what was necessary to help prevent a total collapse of the Iraqi state and further polarization of Iraqi society. Such a reduced but active presence will also send a clear message to hostile countries like Iran and Syria that we intend to remain a key player in this region. The second part of our strategy should be to couple this phased redeployment with a more effective plan that puts the Iraqi security forces in the lead, intensifies and focuses our efforts to train those forces, and expands the numbers of our personnel ? especially special forces ? who are deployed with Iraqi as units advisers. An increase in the quality and quantity of U.S. personnel in training and advisory roles can guard against militia infiltration of Iraqi units; develop the trust and goodwill of Iraqi soldiers and the local populace; and lead to better intelligence while undercutting grassroots support for the insurgents. Let me emphasize one vital point ? any U.S. strategy must address the problem of sectarian militias in Iraq. In the absence of a genuine commitment on the part of all of the factions in Iraq to deal with this issue, it is doubtful that a unified Iraqi government can function for long, and it is doubtful that U.S. forces, no matter how large, can prevent an escalation of widespread sectarian killing. Of course, in order to convince the various factions to embark on the admittedly difficult task of disarming their militias, the Iraqi government must also make headway on reforming the institutions that support the military and the police. We can teach the soldiers to fight and police to patrol, but if the Iraqi government will not properly feed, adequately pay, or provide them with the equipment they need, they will continue to desert in large numbers, or maintain fealty only to their religious group rather than the national government. The security forces have to be far more inclusive ? standing up an army composed mainly of Shiites and Kurds will only cause the Sunnis to feel more threatened and fight even harder. The third part of our strategy should be to link continued economic aid in Iraq with the existence of tangible progress toward a political settlement. So far, Congress has given the Administration unprecedented flexibility in determining how to spend more than $20 billion dollars in Iraq. But instead of effectively targeting this aid, we have seen some of the largest waste, fraud, and abuse of foreign aid in American history. Today, the Iraqi landscape is littered with ill-conceived, half-finished projects that have done almost nothing to help the Iraqi people or stabilize the country. This must end in the next session of Congress, when we reassert our authority to oversee the management of this war. This means no more bloated no-bid contracts that cost the taxpayers millions in overhead and administrative expenses. We need to continue to provide some basic reconstruction funding that will be used to put Iraqis to work and help our troops stabilize key areas. But we need to also move towards more condition-based aid packages where economic assistance is contingent upon the ability of Iraqis to make measurable progress on reducing sectarian violence and forging a lasting political settlement. Finally, we have to realize that the entire Middle East has an enormous stake in the outcome of Iraq, and we must engage neighboring countries in finding a solution. This includes opening dialogue with both Syria and Iran, an idea supported by both James Baker and Robert Gates. We know these countries want us to fail, and we should remain steadfast in our opposition to their support of terrorism and Iran’s nuclear ambitions. But neither Iran nor Syria want to see a security vacuum in Iraq filled with chaos, terrorism, refugees, and violence, as it could have a destabilizing effect throughout the entire region ? and within their own countries. And so I firmly believe that we should convene a regional conference with the Iraqis, Saudis, Iranians, Syrians, the Turks, Jordanians, the British and others. The goal of this conference should be to get foreign fighters out of Iraq, prevent a further descent into civil war, and push the various Iraqi factions towards a political solution. Make no mistake ? if the Iranians and Syrians think they can use Iraq as another Afghanistan or a staging area from which to attack Israel or other countries, they are badly mistaken. It is in our national interest to prevent this from happening. We should also make it clear that, even after we begin to drawdown forces, we will still work with our allies in the region to combat international terrorism and prevent the spread of weapons of mass destruction. It is simply not productive for us not to engage in discussions with Iran and Syria on an issue of such fundamental importance to all of us. This brings me to a set of broader points. As we change strategy in Iraq, we should also think about what Iraq has taught us about America’s strategy in the wider struggle against rogue threats and international terrorism. Many who supported the original decision to go to war in Iraq have argued that it has been a failure of implementation. But I have long believed it has also been a failure of conception ? that the rationale behind the war itself was misguided. And so going forward, I believe there are strategic lessons to be learned from this as we continue to confront the new threats of this new century. The first is that we should be more modest in our belief that we can impose democracy on a country through military force. In the past, it has been movements for freedom from within tyrannical regimes that have led to flourishing democracies; movements that continue today. This doesn’t mean abandoning our values and ideals; wherever we can, it’s in our interest to help foster democracy through the diplomatic and economic resources at our disposal. But even as we provide such help, we should be clear that the institutions of democracy ? free markets, a free press, a strong civil society ? cannot be built overnight, and they cannot be built at the end of a barrel of a gun. And so we must realize that the freedoms FDR once spoke of ? especially freedom from want and freedom from fear ? do not just come from deposing a tyrant and handing out ballots; they are only realized once the personal and material security of a people is ensured as well. The second lesson is that in any conflict, it is not enough to simply plan for war; you must also plan for success. Much has been written about how the military invasion of Iraq was planned without any thought to what political situation we would find after Baghdad fell. Such lack of foresight is simply inexcusable. If we commit our troops anywhere in the world, it is our solemn responsibility to define their mission and formulate a viable plan to fulfill that mission and bring our troops home. The final lesson is that in an interconnected world, the defeat of international terrorism ? and most importantly, the prevention of these terrorist organizations from obtaining weapons of mass destruction -- will require the cooperation of many nations. We must always reserve the right to strike unilaterally at terrorists wherever they may exist. But we should know that our success in doing so is enhanced by engaging our allies so that we receive the crucial diplomatic, military, intelligence, and financial support that can lighten our load and add legitimacy to our actions. This means talking to our friends and, at times, even our enemies. We need to keep these lessons in mind as we think about the broader threats America now faces ? threats we haven’t paid nearly enough attention to because we have been distracted in Iraq. The National Intelligence Estimate, which details how we’re creating more terrorists in Iraq than we’re defeating, is the most obvious example of how the war is hurting our efforts in the larger battle against terrorism. But there are many others. The overwhelming presence of our troops, our intelligence, and our resources in Iraq has stretched our military to the breaking point and distracted us from the growing threats of a dangerous world. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs recently said that if a conflict arose in North Korea, we’d have to largely rely on the Navy and Air Force to take care of it, since the Army and Marines are engaged elsewhere. In my travels to Africa, I have seen weak governments and broken societies that can be exploited by al Qaeda. And on a trip to the former Soviet Union, I have seen the biological and nuclear weapons terrorists could easily steal while the world looks the other way. There is one other place where our mistakes in Iraq have cost us dearly ? and that is the loss of our government’s credibility with the American people. According to a Pew survey, 42% of Americans now agree with the statement that the U.S. should "mind its own business internationally and let other countries get along the best they can on their own.” We cannot afford to be a country of isolationists right now. 9/11 showed us that try as we might to ignore the rest of the world, our enemies will no longer ignore us. And so we need to maintain a strong foreign policy, relentless in pursuing our enemies and hopeful in promoting our values around the world. But to guard against isolationist sentiments in this country, we must change conditions in Iraq and the policy that has characterized our time there ? a policy based on blind hope and ideology instead of fact and reality. Americans called for this more serious policy a few Tuesdays ago. It’s time that we listen to their concerns and win back their trust. I spoke here a year ago and delivered a message about Iraq that was similar to the one I did today. I refuse to accept the possibility that I will have to come back a year from now and say the same thing. There have been too many speeches. There have been too many excuses. There have been too many flag-draped coffins, and there have been too many heartbroken families. The time for waiting in

Iraq is over. It is time to change our policy. It is time to give

Iraqis their country back. And it is time to refocus America’s

efforts on the wider struggle yet to be won. Thank you. |

|

You can only imagine how many different ways people type the name Barack Obama. Here is a sampling for his first name: Barac, Barach, Baracks, Barak, Baraka, Barrack, Barrak, Berack, Borack, Borak, Brack, Brach, Brock even, Rocco. There are just as many for his last name: Abama, Bama, Bamma, Obma, Obamas, Obamma, Obana, Obamo, Obbama, Oboma, Obomba, Obombma, Obomha, Oblama, Omaba, Oblamma and (ready for this?) Ohama. And of course there's Barack Obama's middle name, Hussein. Here are some of the ways it comes out: Hissein, Hussain, Husein, Hussin, Hussane and Hussien.