|

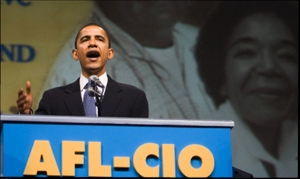

AFL-CIO NATIONAL CONVENTION |

TOPIC: Economy & Labor July 25, 2005 AFL-CIO National Convention Chicago, Illinois Compete Text Thank you, and welcome to Chicago. It would be naive of me to start without acknowledging what's been on everyone's mind during this convention. As America tries to find its way in a global economy, we meet here at a challenging time for the labor movement. There are questions of strategy and tactics, leadership and power. And I can imagine that many of you are anxious not only about labor's future, but yours. You're wondering, will I be able to leave my children a better world than I was given? Will I be able to save enough to send them to college or plan for a secure retirement? Will my job even be there tomorrow? Who will stand up for me in this new world? In this time of change and uncertainty, these questions are expected - but they are by no means unique. From the earliest days of our founding, they have been asked and then answered by Americans who have stood in your shoes and shared your concerns about the future. At the heyday of the Industrial Revolution, millions from around the world flocked to this very city in search of opportunity. Immigrants from Europe, African-Americans from the Jim Crow South, and ethnic groups from every corner of America made their home in these neighborhoods and a living from the mills and factories that crowded a bustling Chicago. The work was brutal and the pay was low, but none more so than on the South Side between Halsted and Ashland Avenue, where you could smell the stench of the meatpacking stockyards from miles away. 50,000 worked in what Upton Sinclair would later call "The Jungle," under some of the most dangerous and oppressive conditions in America. Twice the workers tried to organize, and twice they were ferociously beaten back by employers willing to use violence, race-baiting, and starvation in order to keep wages at 32 cents an hour. But these workers made a choice - a choice that this would not be their future. And so in 1937, as the CIO begin organizing mass industries all across America, meatpacking workers began to follow their lead. Imagine - these people would slave away in these plants all day long, freezing in the winter and sweltering in the summer, watching coworkers get their bones crushed in machines and friends get fired for even uttering the word "union" - and yet after they punched their card at the end of the day, they organized. They went to meetings and they passed out leaflets. They put aside decades of ethnic and racial tension and elected women, African Americans, and immigrants to leadership positions so that they could speak with one voice. They could have accepted their lot in life or waited for someone else to save them. Through their actions they risked life and living. They chose to act. In time, they won. It started with victories as small as putting fans on the factory floor, and ended with paid holidays, and wage increases, and a seniority system, and pensions. It started with hope, and it ended with the fulfillment of a long-held ideal. A humble band of laborers against an industrial giant - an unlikely triumph against the greatest odds - a story as American as any. For this has always been the way with us - at the edge of despair, in the shadow of hopelessness, ordinary people make the extraordinary decision that if we stand together, we rise together. And we do. At the end of the Civil War, when farmers and their families began moving into the cities to work in the big factories that were sprouting up all across America, we had to decide: Do we do nothing and allow the captains of industry and robber barons to run roughshod over the economy and workers by competing to see who can pay the lowest wage at the worst working conditions? Or do we try to make the system work by setting up basic rules for the market, and instituting the first public schools, and busting up monopolies, and fighting so that working people could organize into unions? Through strikes and sit-ins, petitions and rallies, and leaders who kept opportunity alive, we chose to act, and we rose together. Years later, when the irrational exuberance of the Roaring Twenties came crashing down with the stock market, we had to decide: do we follow the call of leaders who would do nothing, or the call of a leader who, perhaps because of his physical paralysis, refused to accept political paralysis? From Roosevelt's decision that political freedom would mean nothing without economic freedom to labor's tireless fight for that same principle, we chose to act - regulating the market, putting people back to work, expanding bargaining rights to include health care and a secure retirement - and together we rose. Today, we face a challenge and a choice once more. Too many of you have seen this challenge up close - when you drive by the old factory around lunchtime and no one walks out anymore. When you can't get that raise or that health care plan you hoped for because your employer is competing with companies who pay foreign workers a fraction of what you make. I saw it during the campaign when I met the union guys who use to work at the Maytag plant down in Galesburg and now wonder what they're gonna do at 55-years-old without a pension or health care; when I met the man who's son needs a new liver but doesn't know if he can afford when the kid gets to the top of the transplant list. It's as if someone changed the rules in the middle of the game and no one bothered to tell them. But as we all know, the rules have changed. It started with technology and automation that rendered entire occupations obsolete. Then companies were able to pick up and move their factories to the developing world, where workers are a lot cheaper than they are in the U.S. Now, advances in technology and communication mean that businesses not only have the ability to move jobs wherever there's a factory, but wherever there's an internet connection. These changes have transformed the American worker into a kind of global free agent - if you can learn the right skills and get a great education, you can out-compete any worker in the world for the high-paying jobs of tomorrow. But it also means that the days of lifetime employment at a company that provided wages, health care, and pensions you can bargain for are coming to an end. At time of such insecurity and vulnerability, there has never been a greater need for a strong labor movement to stand up for American workers. But the question we need to answer is: how will this movement and our people win in this new global economy? Once again, we face a choice. We know that globalization is not just another issue you can be for or against - it's here to stay. And so the question is not whether we can stop it, but how we respond to it. Some answers are clear. When you have an administration that says "no" to a labor-friendly labor board, "no" to organizing rights, "no" to overtime pay, and "no" to a higher minimum wage, you say "no" to that administration and put someone else in office. The Bush Administration's philosophy says we can't do much about the new challenges we face as a nation. And since there is not much to do about global competition, the best that can be done is to give everyone one big refund on their government - divvy it up into individual portions, hand it out, and encourage everyone to use their share to go buy their own health care, their own retirement plan, their own child care, education, and so forth. In Washington, they call this the Ownership Society. But in our past there has been another term for it - Social Darwinism, every man and woman for him or herself. It's a tempting idea, because it doesn't require much thought or ingenuity. It allows us to say to those whose health care or tuition may rise faster than they can afford - tough luck. It allows us to say to the factory workers who have lost their job - life isn't fair. It let's us say to the child born into poverty - pull yourself up by your bootstraps. But there is a problem. It won't work. It ignores our history. It ignores the fact that it has been government research and investment that made the railways and the internet possible. It has been the creation of a massive middle class, through decent wages and benefits and public schools - that has allowed all of us to prosper. It has been the ability of working men and women to join together in unions and demand justice and opportunity that has kept America upwardly mobile. Our economic dominance has always depended on individual initiative and belief in the free market, it has also depended on our sense of mutual regard for each other, the idea that everybody has a stake in the country, that we're all in it together and everybody's got a shot at opportunity. So part of the fight is political - and part of the solution is to strengthen the right to organize across all industries and professions. But it's not enough just to say "no" to Bush. They may not have helped, and they may have made things worse, but they did not cause globalization. And no matter what comes out of this convention, the labor movement must squarely confront the fact that the economy is changing. The old ways of doing business are not working, and we must have a strategy that meets these new challenges. I won't stand up here and say that coming up with this strategy will be easy, or pretend to know all the answers. But part of the answer is recognizing that while unions and government can no longer provide this opportunity in the form of lifetime employment; they can ensure that every American worker has lifetime employability in this new economy. That means fixing our schools to make sure every child in America has the education and the skills they need to compete - and that college is affordable for every American who wants to go. And it means that unions can play a real role in finally creating a real system of lifelong learning so that workers who lose a job really can retrain for other high-wage jobs.

Right now, all across America, there are amazing discoveries being made. At Pittsburgh's Carnegie Mellon University, researchers have developed a virtual algebra tutor that has helped inner-city kids in under-served schools raise their scores an entire letter grade. In rural Virginia, telemedicine recently allowed a cardiologist 75 miles from the hospital to view an ultrasound and diagnose a congenital heart defect that required immediate medication, saving a young child's life. And in the very cornfields of Illinois, farmers are literally growing the biofuels that could ultimately run our cars on 500 miles per gallon. Breakthroughs like these won't just improve our lives, they'll create thousands of jobs that could be filled by American workers trained with new skills and a world-class education. In this new economy, we should be able to tell workers that no matter where you work or how many times you switch jobs, you will have health care and a pension you can take with you always. We'll never rise together if we allow medical bills to swallow family budgets or let people retire penniless after a lifetime of hard work, and so today we must demand that when it comes to commitments made to working men and women on health care and pensions, a promise made is a promise kept. Our vision of America is not one where a big government runs our lives; it's one that gives every American the opportunity to make the most of their lives. It's not one that tells us we're on our own, it's one that realizes that we rise or fall together as one people. And yet, we also know that, in the end, neither policy nor politics can replace heart and courage in the struggle you now face. Because in the brief history of the American experiment, it has been the ability of ordinary Americans to act on both that has allowed our nation to achieve extraordinary things. It's why farmers put down their ploughs and picked up arms to overthrow an Empire for the sake of an idea. It's why young men and women would take Freedom Rides down South to work for the Civil Rights movement. And it's why workers would stand cold, hungry, and penniless on picket lines until their labor was treated with the dignity it deserved. Almost a century earlier, during the struggle for the soul of Chicago's stockyards, Hank Johnson, a leading African-American union organizer, told a crowd of laborers that in the end, speeches don't make unions. He said that "The real job of organizing has to be done everyday by the men and women who work right in the plant." That's as true

today as it was then - the real job of organizing working America

- politics and policy, vision and mission, heart and soul - belongs

to each of you. And if you have the courage to succeed, labor will

rise again. America will rise again. And hope will rise again. Thank

you and God Bless you. |

|

You can only imagine how many different ways people type the name Barack Obama. Here is a sampling for his first name: Barac, Barach, Baracks, Barak, Baraka, Barrack, Barrak, Berack, Borack, Borak, Brack, Brach, Brock even, Rocco. There are just as many for his last name: Abama, Bama, Bamma, Obma, Obamas, Obamma, Obana, Obamo, Obbama, Oboma, Obomba, Obombma, Obomha, Oblama, Omaba, Oblamma and (ready for this?) Ohama. And of course there's Barack Obama's middle name, Hussein. Here are some of the ways it comes out: Hissein, Hussain, Husein, Hussin, Hussane and Hussien.